Online Shop

130

Royal Horticultural Society

Gold Medals

Royal Horticultural Society

Gold Medals

- Home

- About Bowdens

- Dick Hayward

- Pilgrimage to Culcita by Dick Hayward - Chamaerops 20

Pilgrimage to Culcita by Dick Hayward - Chamaerops 20

A delightful article by a real enthusiast about a trip to Spain and an attempt to locate one of Europe's rarest and most exciting Treeferns – from Chamaerops 20 Autumn 95, the Journal of the European Palm Society.

With a title like the above you might anticipate that you are about to hear of a journey to the fabled ruins of some ancient Inca temple in Peru, or perhaps of a call to pay homage to an ageing beauty, one-time mistress of a famous but long-dead Spanish grandee. Neither conjecture will be sustained. We shall certainly be going to Spain and, by pure accident, Culcita does have a very Spanish ring to it. In fact, the object of my little pilgrimage this summer was a magnificent stand of ferns in the noun- but even more beautiful tree fern Cyathea dealbata, Culcita has been described as a genus of primitive tree ferns. The only species native to Europe is C. macrocarpa, its ten or so brethren being inhabitants of generally more tropical climes. Indeed, the amazing thing about our Citatains of Asturias, outliers to the wonderful Picos de Europa, the 'Mountains of Europe', so named by Spanish mariners returning from the New World who seeing the mountains would know themselves to be close to a landfall on their home coasts.

A fascination for ferns dates back to about age thirteen when absolutely intrigued by a 'flowering' clump of our native Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis) growing on a cliff face in Cornwall, I felt compelled to slide down a rope, claw it out of its crevice and take it home to a North London garden. It thrived wonderfully, and I was hooked for life as a 'pteridophytophile' - or, as Martin Gibbons proposed, a 'pterodactyl'. This was a very long time before palms came to secure a big corner of my affections. Yet ferns and palms are really so similar in the gross visual plan that bigamous affections ought to be easily appreciated. A psychologist with a biological background might describe it as 'a fixation on radial symmetry', and, quite apart from an ever-present susceptibility to the lure of the exotic in plants, it would account for a weakness for agaves, aloes and bromeliads. I hope dyed-in-the-wool palm enthusiasts will not take it amiss if I say that not only is your fern freak a potential palm nut, but conversely, that inside even the most monolithic palm nut there could be lurking a pterodactyl!

A member genus of the Dicksoniaceae, a family which includes the familiar Dicksonia antarctica as well as the somewhat less familiar European Culcita is that it is still here, for it is a member of a relict flora of a once sub-tropical Europe which came to an end in the late Tertiary glaciations of a million years ago. Although far better preserved in the islands of the Atlantic (Madeira, the Canaries and Azores), this beautiful plant still survives in a handful of protected locations in the Iberian Peninsula. For very good reasons, such sites are not public knowledge and I count myself very lucky to have been given reasonably explicit instructions on how to find one of them. A day devoted to this enterprise was to be the culmination of a mountaineering holiday in Los Picas. The high Picos are a glorious place for the naturalist and on my every visit I am amazed that such an arid lunar landscape, with its upland valleys devoid of streams and its high corries without lakes, can support such a variety of plant and animal life. Ferns such as the Holly Fern (Polystichum tonchitis), Green Spleenwort (Asplenium viride) and Rigid Buckler (Dryopteris submontana), all so rare in Britain, abound here, while in places the walls of the lower valleys, which do have rivers, are thick with the European Maidenhair (Adiantum copillusveneris). The limestone gorges here look so like those near Ronda in Andalucia that it is a disappointment not to find Chamaerops humilis bursting out of cracks in the rocks, as it often does there. But this area gets less sun and much more rain.

Down from the mountains and exchanging the doubtful joys of backpacking for the comfort of a hire-car, we celebrated our return to the valleys with a suitably vinous lunch before starting our serious quest for ferns. I say 'our' and I must introduce my companion Owen, whom I knew even before the advent of Osmunda. Each year we engage in a ritual of pitching tiny tents in wild windswept places, haul ourselves up ridges and gullies, and limp home declaring we've had a wonderful holiday. Although a keen plantsman, Owen is not a signed-up fern freak, and his preferred part in our searches is to drive me around while I scan the passing plant life and call a halt when closer scrutiny is invited. Over and above the role of chauffeur, he manages to call up vast reserves of long-suffering whilst I disappear for hours into bogs and thickets. This year there was to be a second day of this sort of thing with, for me, the possible highlight of finding Culcita. For this degree of commitment, plus the fact that he undertook to record proceedings on film, Owen must at least deserve status as an honorary pterodactyl!

The second day was overcast and humid. Our instructions took us deep into some fairly out-of-the-way country prettily wooded with chestnut, oak and eucalyptus and endowed with a great variety of ferns. It was close to midday before we reached a place that seemed to match the description on our pencilled sketch-map. Dropping down into the cleft of a muddy stream bed I worked my way through the brambly undergrowth which hugged its banks. Overhung with tall trees and a skirt of high bracken on its steep far side the place was quite dark, close and sticky. (The time was early August and the height of our 1995 heat wave.) Half an hour later and just when I was beginning to wonder if we'd misread the map, quite suddenly there she was, the object of our pilgrimage! Magnificent plants! Intricately divided leathery fronds, almost blueygreen in colour, widely triangular and held high on blackish red-haired stipes (frond-stems) almost an inch thick. The European Garden Flora and Flora Europaea both record the frond size as between 30 and 90 cms, but I had been told to expect specimens much larger, and they were; many fronds being close to 2 metres. Standing among these luxuriantly tropical plants - so unlike any other fern in Europe - was to re-live feelings I had experienced on a trip to Java.

In comparison with the acres of bracken and bramble above the cleft the few square yards allowed to these clumps of Culcita say much about the precariousness of its tenancy in mainland Europe. We had come a long way to see these few square yards and we did not return disappointed, knowing well that the essence of a shrine is never to be measured with a yardstick.

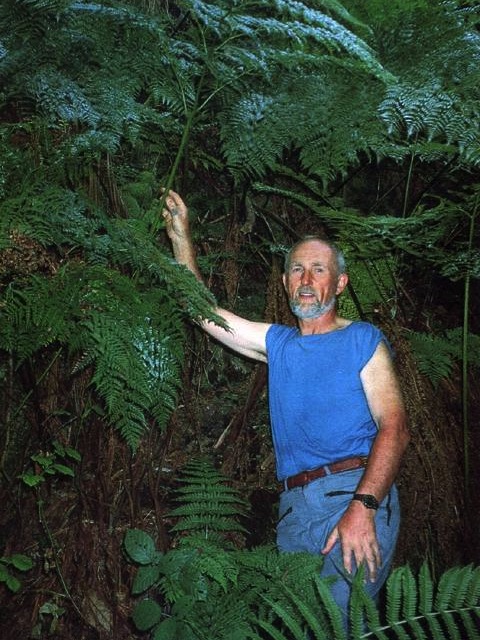

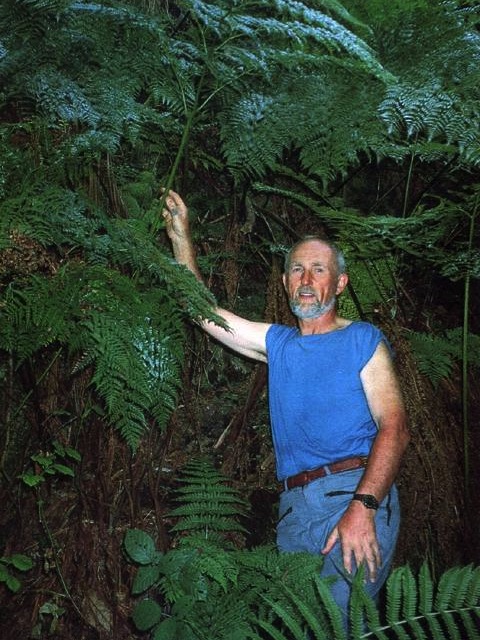

Pilgrim's Progress: Dick Hayward and Culcita macrocarpa

With a title like the above you might anticipate that you are about to hear of a journey to the fabled ruins of some ancient Inca temple in Peru, or perhaps of a call to pay homage to an ageing beauty, one-time mistress of a famous but long-dead Spanish grandee. Neither conjecture will be sustained. We shall certainly be going to Spain and, by pure accident, Culcita does have a very Spanish ring to it. In fact, the object of my little pilgrimage this summer was a magnificent stand of ferns in the noun- but even more beautiful tree fern Cyathea dealbata, Culcita has been described as a genus of primitive tree ferns. The only species native to Europe is C. macrocarpa, its ten or so brethren being inhabitants of generally more tropical climes. Indeed, the amazing thing about our Citatains of Asturias, outliers to the wonderful Picos de Europa, the 'Mountains of Europe', so named by Spanish mariners returning from the New World who seeing the mountains would know themselves to be close to a landfall on their home coasts.

A fascination for ferns dates back to about age thirteen when absolutely intrigued by a 'flowering' clump of our native Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis) growing on a cliff face in Cornwall, I felt compelled to slide down a rope, claw it out of its crevice and take it home to a North London garden. It thrived wonderfully, and I was hooked for life as a 'pteridophytophile' - or, as Martin Gibbons proposed, a 'pterodactyl'. This was a very long time before palms came to secure a big corner of my affections. Yet ferns and palms are really so similar in the gross visual plan that bigamous affections ought to be easily appreciated. A psychologist with a biological background might describe it as 'a fixation on radial symmetry', and, quite apart from an ever-present susceptibility to the lure of the exotic in plants, it would account for a weakness for agaves, aloes and bromeliads. I hope dyed-in-the-wool palm enthusiasts will not take it amiss if I say that not only is your fern freak a potential palm nut, but conversely, that inside even the most monolithic palm nut there could be lurking a pterodactyl!

A member genus of the Dicksoniaceae, a family which includes the familiar Dicksonia antarctica as well as the somewhat less familiar European Culcita is that it is still here, for it is a member of a relict flora of a once sub-tropical Europe which came to an end in the late Tertiary glaciations of a million years ago. Although far better preserved in the islands of the Atlantic (Madeira, the Canaries and Azores), this beautiful plant still survives in a handful of protected locations in the Iberian Peninsula. For very good reasons, such sites are not public knowledge and I count myself very lucky to have been given reasonably explicit instructions on how to find one of them. A day devoted to this enterprise was to be the culmination of a mountaineering holiday in Los Picas. The high Picos are a glorious place for the naturalist and on my every visit I am amazed that such an arid lunar landscape, with its upland valleys devoid of streams and its high corries without lakes, can support such a variety of plant and animal life. Ferns such as the Holly Fern (Polystichum tonchitis), Green Spleenwort (Asplenium viride) and Rigid Buckler (Dryopteris submontana), all so rare in Britain, abound here, while in places the walls of the lower valleys, which do have rivers, are thick with the European Maidenhair (Adiantum copillusveneris). The limestone gorges here look so like those near Ronda in Andalucia that it is a disappointment not to find Chamaerops humilis bursting out of cracks in the rocks, as it often does there. But this area gets less sun and much more rain.

Down from the mountains and exchanging the doubtful joys of backpacking for the comfort of a hire-car, we celebrated our return to the valleys with a suitably vinous lunch before starting our serious quest for ferns. I say 'our' and I must introduce my companion Owen, whom I knew even before the advent of Osmunda. Each year we engage in a ritual of pitching tiny tents in wild windswept places, haul ourselves up ridges and gullies, and limp home declaring we've had a wonderful holiday. Although a keen plantsman, Owen is not a signed-up fern freak, and his preferred part in our searches is to drive me around while I scan the passing plant life and call a halt when closer scrutiny is invited. Over and above the role of chauffeur, he manages to call up vast reserves of long-suffering whilst I disappear for hours into bogs and thickets. This year there was to be a second day of this sort of thing with, for me, the possible highlight of finding Culcita. For this degree of commitment, plus the fact that he undertook to record proceedings on film, Owen must at least deserve status as an honorary pterodactyl!

The second day was overcast and humid. Our instructions took us deep into some fairly out-of-the-way country prettily wooded with chestnut, oak and eucalyptus and endowed with a great variety of ferns. It was close to midday before we reached a place that seemed to match the description on our pencilled sketch-map. Dropping down into the cleft of a muddy stream bed I worked my way through the brambly undergrowth which hugged its banks. Overhung with tall trees and a skirt of high bracken on its steep far side the place was quite dark, close and sticky. (The time was early August and the height of our 1995 heat wave.) Half an hour later and just when I was beginning to wonder if we'd misread the map, quite suddenly there she was, the object of our pilgrimage! Magnificent plants! Intricately divided leathery fronds, almost blueygreen in colour, widely triangular and held high on blackish red-haired stipes (frond-stems) almost an inch thick. The European Garden Flora and Flora Europaea both record the frond size as between 30 and 90 cms, but I had been told to expect specimens much larger, and they were; many fronds being close to 2 metres. Standing among these luxuriantly tropical plants - so unlike any other fern in Europe - was to re-live feelings I had experienced on a trip to Java.

In comparison with the acres of bracken and bramble above the cleft the few square yards allowed to these clumps of Culcita say much about the precariousness of its tenancy in mainland Europe. We had come a long way to see these few square yards and we did not return disappointed, knowing well that the essence of a shrine is never to be measured with a yardstick.

New Additions

-

Wundergold £15.00

-

Unruly Child £14.00

-

Twin Cities £14.00

-

Valley's Love Birds £14.00

-

Valley's Lemon Squash £14.00